Hello.

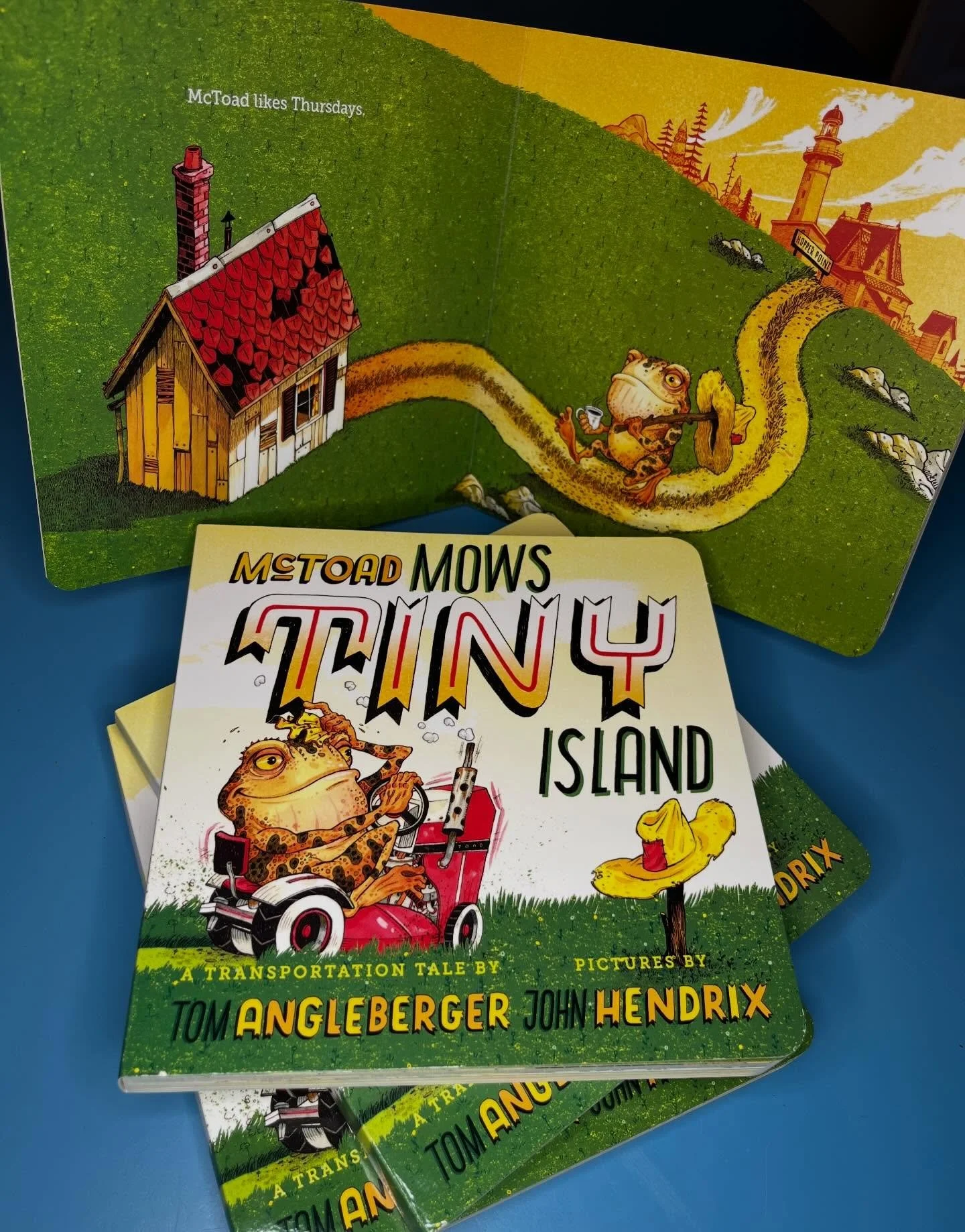

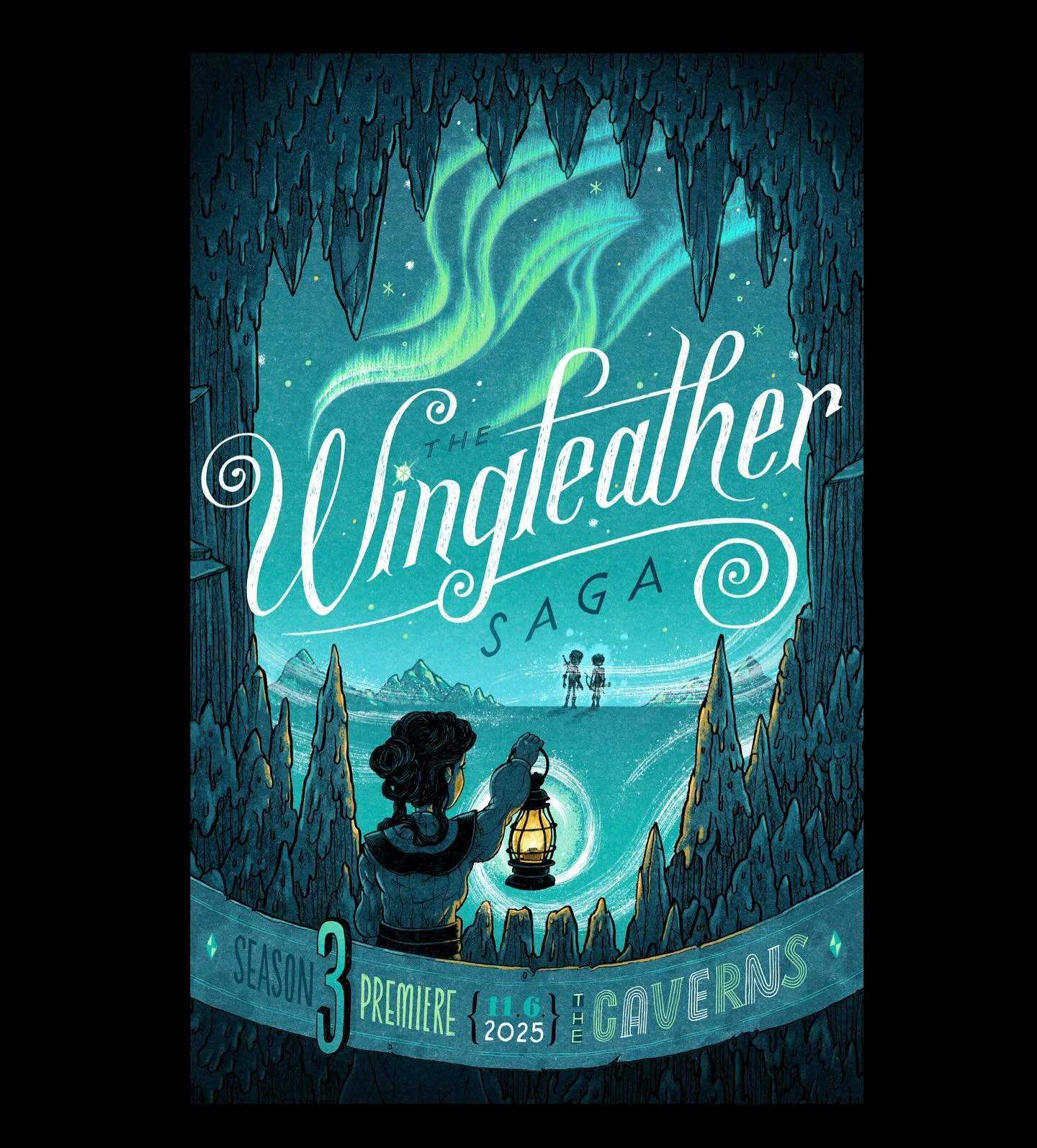

John Hendrix is a New York Times bestselling author and illustrator. His books include The Faithful Spy: Dietrich Bonhoeffer and the Plot to Kill Hitler, called a Best Book of 2018 by NPR, Drawing Is Magic: Discovering Yourself in a Sketchbook, The Holy Ghost: A Spirited Comic, Miracle Man: The Story of Jesus, and many others. His award-winning illustrations have also appeared on book jackets, newspapers, and magazines all over the world. John’s Eisner nominated graphic novel, The Mythmakers: The Remarkable Fellowship of C. S. Lewis and J. R. R. Tolkien, about the literary and spiritual friendship between Lewis and Tolkien, was named a Best Children’s Book of 2024 by The New York Times. In his review for The New York Times Book Review, bestselling author Lev Grossman called The Mythmakers “eloquent prose and charming, expressive drawings.” John is the Kenneth E. Hudson Professor of Art and the founding chair of the MFA in Illustration and Visual Culture program at the Sam Fox School of Design and Visual Arts at Washington University in St. Louis. In 2021, 3x3 Magazine named John the Educator of the Year in illustration. The Society of Illustrators named John the Distinguished Educator in the Arts for 2024,

John’s work has appeared in numerous publications, such as Newsweek, Sports Illustrated, Entertainment Weekly, Rolling Stone, The New Yorker, Esquire, The New York Times, and Time Magazine, National Geographic, among many others. He has also drawn book jackets for the likes of Scholastic, Random House, Simon & Schuster, Harper Collins, Greenwillow Books, Knopf, Penguin, and Abrams Books. His images also appeared in advertising campaigns for ESPN/ABC, AT&T, Pfizer, and Target. John’s books have won numerous awards, including a Gold Medal from The Society of Illustrators for The Faithful Spy in 2018. That project was also named a "Best Book of 2018" by National Public Radio (NPR) and was named a YALSA Nonfiction medal finalist from American Library Association (ALA). His drawings have also appeared in the annual award publications, 3x3, American Illustration, Society of Illustrators, Society for Publication Design, Communication Arts, AIGA 50 Books/50 Covers Show, and Print’s Regional Design Annual.

In 2012, John served as President of ICON7- The Illustration Conference, a biennial global summit for the illustration community, and before that as Vice President of ICON6 in 2010. John also chaired The Society of Illustrators 55th Annual Show- the illustration industry's longest running and most prestigious juried show.

His first picture book Abe Lincoln Crosses a Creek, was named and ALA Notable book of 2008 and won the Comstock Award for read aloud books. John’s book, John Brown: His Fight for Freedom the first he had both written and illustrated, won the Oppenheim Toy Portfolio Gold Seal and was named one of the “Best Books of 2009” by Publisher’s Weekly. About his 2016 book "Miracle Man: The Story of Jesus," the New York Times said, " ... even nonbelievers will enjoy this powerfully told and visually dazzling book."

Born in the gritty midwestern suburbs of St. Louis, John attended The University of Kansas to study graphic design and illustration. He graduated with a degree in Rock Chalk and Visual Communication in 1999. After working for a few years as a designer, John moved from Kansas to New York City. John attended The School of Visual Arts MFA “Illustration as Visual Essay” program and graduated in 2003 with some honors and some debt. During his time living and working in New York, John taught design at the Parsons School of Design and worked at The New York Times as Assistant Art Director of the Op-Ed page for several years.

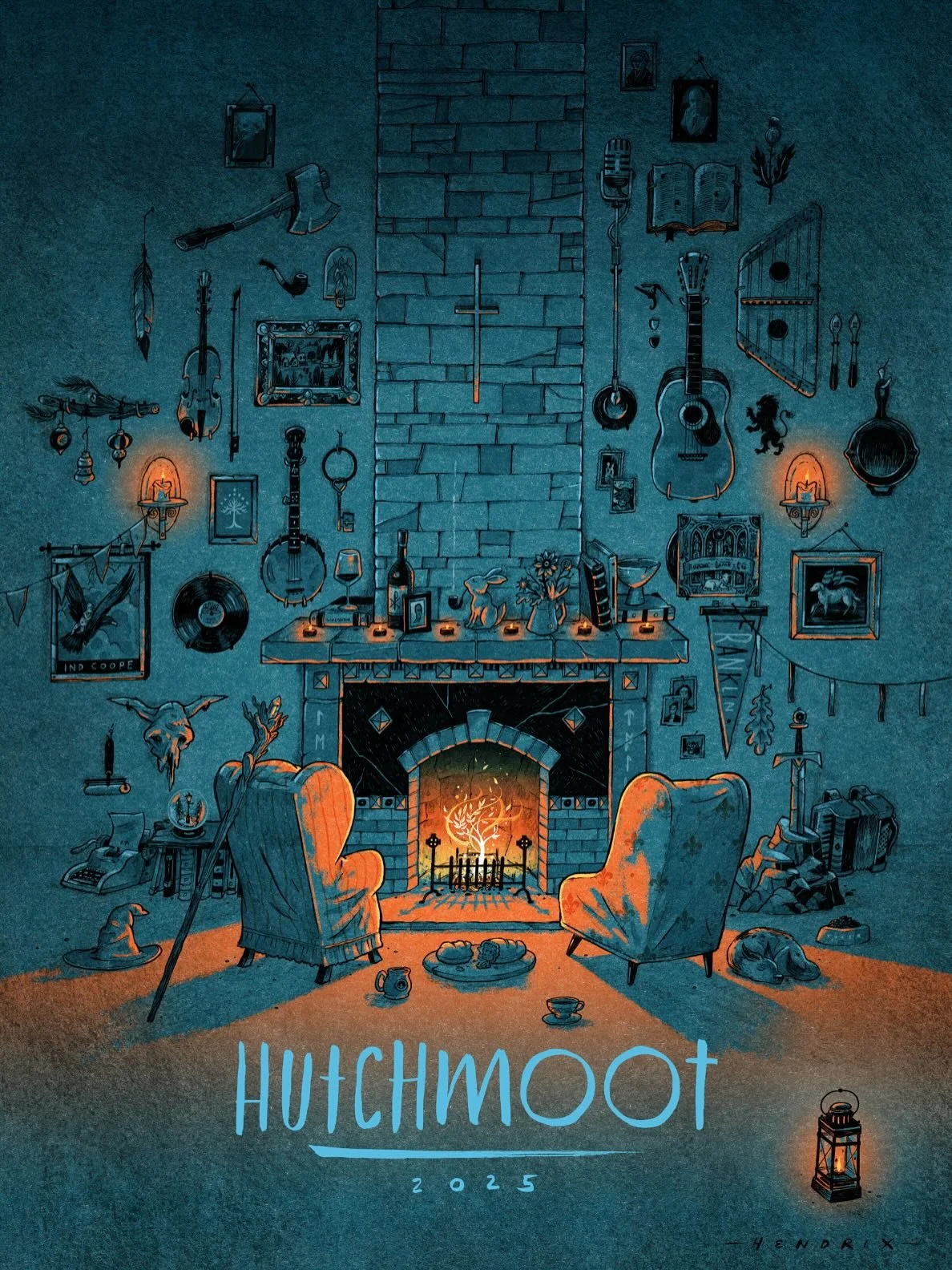

John has presented his work and drawings in many places: San Diego Comic Con, The National Archives in Washington D.C., the Texas Library Association, ABA’s Children’s Institute, Miami Book Festival, The Festival of Faith & Writing, Hutchmoot: The Rabbit Room's Annual Conference of art, music and faith, The Southern Festival of Books, SCBWI Conference, Church NEXT Conference - Story Conference, Nashville - Q Commons St. Louis, The National World War I Museum, among many others. John's sketchbook drawings from church have been featured in Christianity Today and Smithsonian Magazine. John lives in the St. Louis, with his wife Andrea, son Jack and daughter Annie, dog Pepper and cats Kit-Kat and Luna.

ABOUT MY WORK

As an illustrator, I aim to communicate clear ideas using images made with pen and ink on paper. The heart of my practice has always been, simply, making drawings. But, I have come to realize the real activity at the center of the wheel lies beyond the drawing—in the act of translation. Similar to adaptation, a visual translation extends and transforms the existing content. An image that is paired with text is not merely a pictorial caption. Illustration fuses both word and image into a single whole; creating entirely new paths for accessing ideas, learning history, describing experiences, and communicating stories.

Though much of my work today centers on the craft of writing and illustrating stories for young people, a segment of my practice represents a segment of the illustration field called 'editorial illustration.' My career began in this world, working from articles and essays in print periodicals like The New York Times, Newsweek, The New Yorker, Time, Rolling Stone and many others back in the mid 2000s. I still make time for editorial works alongside my books and comics because this kind of pictorial algebra is deeply enjoyable. Illustration at its best is a lens for seeing ideas in a new way—a translation from the verbal to the visual.

Photo by Whitney Curtis

Interviews, Podcasts, and Features

Q&A with John

Tell us a bit about your background, were you always interested in illustration?

I can’t remember a time in my life before drawing. The act of drawing is a foundational part of my identity and how I process the world. But, the notion of “illustration” as a category of picture or creative activity didn’t really register until, embarrassingly, during my undergraduate design education. Now, I always looked at illustrations, in children's books, illustrated novels and comics- but the particular taxonomy of Illustration as a both process and artifact was something I had to be taught to see.

Where did you attend college? What was that experience like?

My undergraduate experience was at the University of Kansas, where I studied Visual Communications. I met Barry Fitzgerald, an amazing teacher and role-model for a life in illustration and the academy. After a few years, I moved to New York City, to attend the MFA Illustration and Visual Essay program at School of Visual Arts. I met so many amazing illustrator-educators there, including Marshall Arisman, David Sandlin, Wes Bedrosian, Carol Fabricatore, and Carl Titolo among many others.

What were your early impressions of illustration? Were there any particular artists who influenced your decision to become an illustrator?

I loved pictures, that’s all I knew. Anything that told a visual story or explained something visually was catnip. David MacCauley’s books “Cathedral” and “The Way Things Worked” were critical influences of visually explaining complexity. They made me realize that I learned so much better through images than I did textually. I was obsessed with J.R.R. Tolkien and the illustrations from various editions of The Hobbit. The early Bugs Bunny cartoons, art of Chuck Jones, Friz Freleng, Tex Avery, were influences on my drawing as a child. I would copy Garfield comics right out of the newspaper. Of course, Star Wars, as both a visual idea and a story, are so critical to my love of art making and my desire to do that for the rest of my life. The comics I read I did almost entirely for the art. I followed artists from book to book, eager to find new art to copy and emulate. From the original Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles by Eastman and Laird, to Todd MacFarlane’s Spiderman, I was obsessed with form more than even stories.

What happened after graduation?

Like most young artists, nothing happened the way I had imagined. “Becoming an illustrator” was a much longer process than I expected. I started working as a junior designer in a PR firm, Fleishman-Hillard in Kansas City. I only lasted 10 months in corporate America! After that, I joined a smaller boutique design firm called North Company in Lawrence, Kansas. That was a much better fit for me, but it was still not what I had dreamed of doing, which was drawing for a living. I longed to be writing and illustrating my own works. Teaching as a vocation had not even dawned on me yet.

What brought you to The School of Visual Arts graduate program?

One particularly hard day, I remember my wife Andrea saying, “we should just go to New York, we should do it, you should go back to school.” Seems crazy, but I felt I had ‘missed’ my chance to be an illustrator at age 25. So, I only applied to one school: School of Visual Arts, because to me it was NYC or bust. At this point, New York was the capital of everything I wanted. I traveled to New York for the first time as part of a Graphic Arts Festival in the fall of 2000. It was like a perfect fall New York weekend. I’ll never forget it. I went to see the school on a visit and met Marshall, and that same weekend I met Steven Guarnaccia. I toured Push-Pin Studios. I even met Seymour Chwast and we went to the offices of Entertainment Weekly, and toured Rolling Stone. I had lunch with Guy Billout! I was smitten with the city and the field of illustration.

How did you get your first big break?

My first real job came from Minh Uong, at the Village Voice- and it was a total disaster. I got a few big jobs my first year, a four page gate-fold from Sports Illustrated and an album review for Rolling Stone for the Beastie Boys. But, when I think about my big break, it has to be that I (somehow!) was hired as an assistant art director on the Op-Ed page of The New York Times. Steven Guarnaccia was my boss, and I learned so much from him. He was a mentor that changed my life. I still cringe when I think of some of my early mistakes at the paper, but I met so many artists and art directors. Importantly, I learned how to think quickly and work with editors and major deadlines. Later I worked with Brian Rea, Steven Heller, and many other legends. It was like the ‘extreme sport’ version of illustration and I loved every minute. Still miss that place!

How has your work progressed, how is today’s work different from when you were first starting out?

Over the years, I think the core of my visual voice has remained more or less the same, but the formal qualities have changed. I used to work nearly 100% analog on every project, and though I aspire for all my work to feel like it could have been made totally by hand, I use digital tools for a big portion of my process. I also have gravitated over the years to more graphic compositional choices and use of 2-color solutions which I didn’t have much experience with earlier on in my career. The feeling of pen on paper, the simple arithmetic of artist+pen+paper = idea is at the center of what I aspire for my work to embody.

In addition to your editorial work, you have also published a number of children’s books. How is your approach different from other illustrator’s books for young readers?

My books that I have written and illustrated usually focus on moments of moral gravity, of one kind or another. Increasingly engaging issues surrounding the Christian faith. From the story of German Lutheran preacher turned Hitler assassin, Dietrich Bonhoeffer, to the life of religious abolitionist John Brown, I’ve used biography as a narrative vessel to unpack ideas of ethics, citizenship, theology, and history. I am not sure my approach is totally unique, but I have carved out a very clear space in the book industry.

I also believe that my works are more like translation than creation. I am in awe of truly world-building generative creators, as much of the work I loved as a child best falls into this category. But that is really not part of my gifts, even though I have tried. My works aspire towards clarity. When telling stories to children, especially challenging narratives from history, there is value in communicating complexity. We must never simplify history for our young audiences, we must take the complex and make it clear. I consider clarity my vocational calling in my authored works.

Tell us about your graphic novel: The Mythmakers: The Remarkable Fellowship of C.S. Lewis & J.R.R. Tolkien.

The story of writing The Mythmakers was really a love letter to C.S. Lewis and J.R.R. Tolkien. I owe them so much in my own creative life, they really validated imagination as a real thing that was worth investing in and thinking about and writing about. So that's where the seed of the book came from. I have way too many ideas for books, and the problem is figuring out which book or which idea I'm going to spend so much time on, and this was a story that I knew very early on I needed to make happen.

Why are mythic narratives still essential to understand our own stories? The title even mentions the concept of a “myth-maker,” what does that mean?

To tell the story of Lewis and Tolkien, you must understand their shared faith. While they were different in the sense that was a Catholic and Lewis grew up as an Anglican (though when they meet he was an atheist.) What they shared was a belief, and a longing, to be a part of a greater story. In the book I talk about this pivotal conversation that Lewis and Tolkien had on Addison’s Walk, on the grounds of Oxford in September of 1929. They talked for hours, late into the night, about the nature of story, myth and God. The title of my book, “The Mythmakers” is a reference to this pivotal moment. Tolkien famously convinced Lewis that humanity writes myths, not because we long to be told comforting lies, but because our hearts were created by a Mythmaker. “We make in the manner in which we were made,“ Tolkien said. This single notion was the turning of the key in Lewis’s heart. It allowed him to write the rest of his works. Scholar Alan Jacob says that Lewis was convinced that the Christian story was true not by a set of facts but by “learning to see a story the right way.”

What are some of your favorite books for children?

Where to start! As I mentioned above, my life was changed by a few books early on, namely: David MacCauley’s “Cathedral” and “The Way Things Work” various illustrated editions of J.R.R. Tolkien’s “The Hobbit” and the Pauline Baynes illustrated versions of "The Chronicles of Narnia,” by C.S. Lewis. As a child I loved complicated board games, and the archaic rule sets of things like D&D and Star Wars roleplaying games. They allowed me to think about entire systems and worlds and how they functioned. It is impossible not to include Calvin and Hobbes. My writing voice in comics is so closely aligned with Bill Watterson I should probably send him royalty checks. As for more recent books, it is hard to pick a set of my favorites. I love the author illustrators like Adam Rex, Jillian Tamaki, Brian Floca, Dan Santat, Sophie Blackall, and Jon Klassen. I’ve always been in awe of the audacious books of Shaun Tan, and I think Brian Selznick’s “The Invention of Hugo Cabret” is a formal masterpiece. Also, Carson Ellis’s “Du Iz Tak?” is something I wish I had had made, it is such a perfect book for children.

How do you think about writing religious material?

Every person, whether they recognize it or not, has a set of “first principles.” These are the frameworks by which we move, engage others, and make decisions. Said another way, a set of beliefs that animate each person’s worldview. It is different for every person, for me my Christian faith is that set of principles. A good summary of this for me is a quote from C.S. Lewis, “I believe in Christianity as I believe that the sun has risen: not only because I see it, but because by it I see everything else.” So, it was not a mere ‘flavor’ that I brought to my work, or a way to sell books to a certain audience. It is the foundation that my life (and therefore my work) is built upon. Over the years, the faith elements have become more prominent in my writings, but I also don’t feel limited to work on other subject areas either. In some ways, the religious themes have come out not by design but simply it was impossible to suppress them from what I found most interesting and most essential to my interior life.

As a teacher, I often am in the position of helping younger artists find their artistic voice. I always remind them that the things we think about are the things we make art about. At some point, if you spend an enormous amount of energy reading and reflecting on any material, it is only a matter of time before that stuff finds its way into your work.So, this is another way for me to answer your question. For years, I was listening to sermons, singing hymns, reading theology, and the Bible. I never intentionally decided to make a ‘religious book,’ but rather, my writing and ideas reflected the world I was inhibiting already. As Annie Dillard said, famously, “How we spend our days, is of course, how we spend our lives.”

As an author/illustrator what do you feel your responsibilities are telling stories that might be considered controversial for young children, i.e. John Brown?

Yes, I do think there is a responsibility to all storytelling, especially history. It is easy to perpetuate assumptions and narratives about our past. When telling stories to children, the danger is even more acute. It is tempting to gloss over and sanitize. Now, there are certain things that an age group should not be exposed to, for their own protection and conceptual development. That said, we should not shield children from engaging in moral complexity or conversations about purpose, meaning and ethics. We must tell the truth, the hard truth, but in ways that protect young minds from disturbing details they are not ready to engage.

How would you describe your creative process? Especially with your books, do you start with a clear vision, or does the work take shape as you go?

The first thing you should know is that all my projects start out as just a huge mess. The process is very organic. I write to get at the pictures in my head. In many ways, I'm a sort of an accidental author. I did not like writing when I was in high school, I found it very difficult, and so the 14-year-old version of myself would be shocked that I have an author usually listed as the first thing in my bio! I would say first about myself that I'm an artist, and yes, my first ideas come as images. So, I'm an accidental writer, and I'm also an accidental researcher. I wanted to write books about people like John Brown or Dietrich Bonhoeffer or whoever I was interested in, and I realized that to do that, I've got to read a lot and I've got to find a way to catalog and index that information so that I can use it in some way down the road. Really, I learned all those researching lessons the hard way, through experience.

To work out the story I like to make a giant visual chart of everything, something that I can flip through in a notebook or reference very quickly on the wall. I always read in paper copies of research books and as I'm reading, I just draw all over the book. I mean, I'll make sketches, flag pages, and put stickies in it. I create a visual index system that I can quickly flip through and remember great quotes or ideas. So then those books become really essential. Once I mark up a book, it's my most valuable piece of intel.

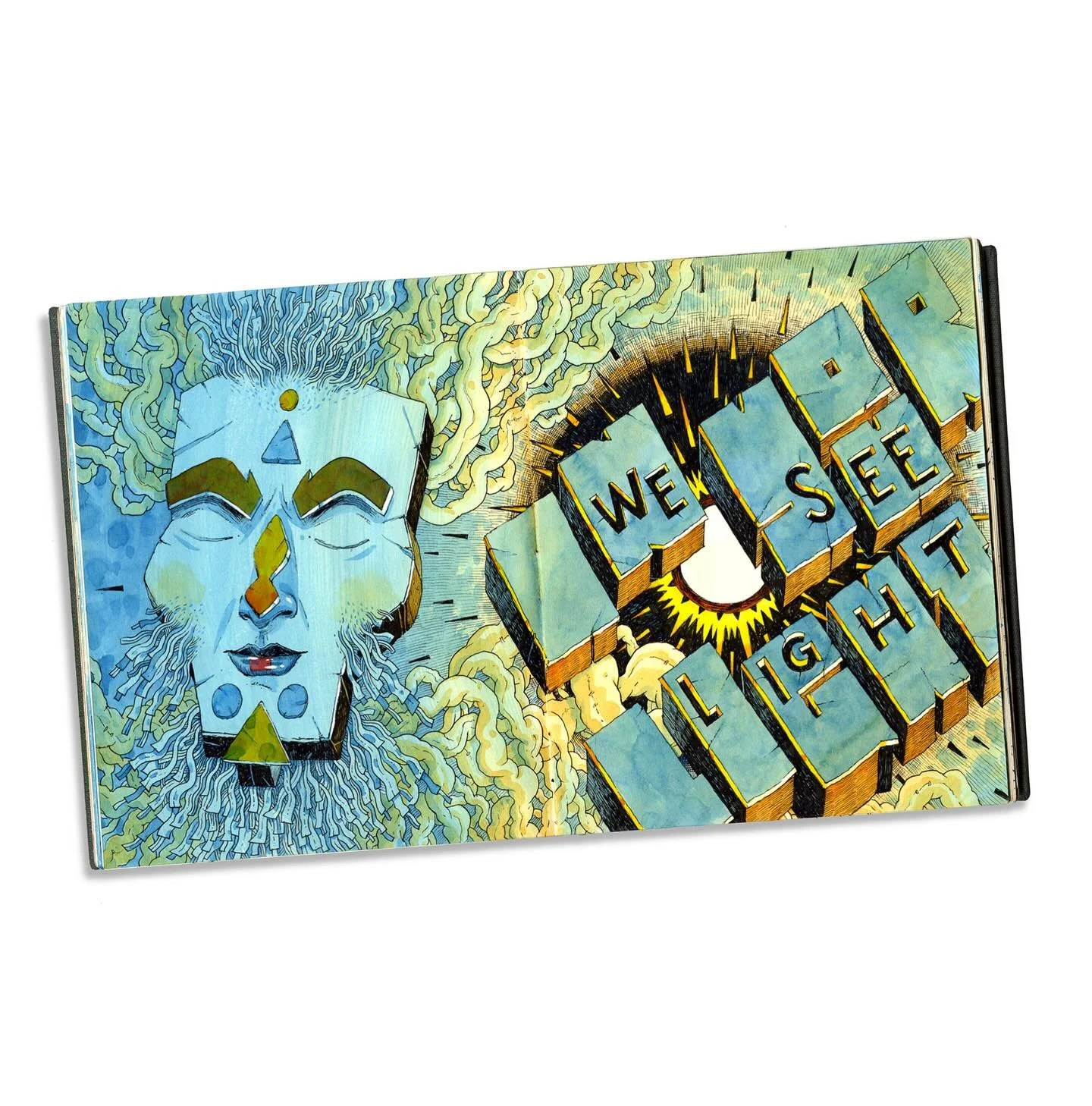

Your current work includes images coupled with quite a bit of hand lettering, why?

I love type! But there are two strands to think about with drawing type in your work, it works as both form and communication. I enjoy letterforms as a formal element to activate my drawings for this reason: when you can sink the communication behind the formal play, it inverts our normal relationship with type. Usually, when we see type, we read the word, rather than see its physical form. By drawing type as objects, it creates a new space for type in imagery. This unity of word + image, in my mind, creates a new third space that neither type or image can accomplish on its own. Occasionally I’ll have an art director ask me *not* to put words in my pictures for an editorial reason, and I find it very hard to come up with ideas. Usually I just ignore it, then remove the letters later. So, I’ve found my generative process actually relies on the ballet of word and image relationships.

Let’s talk about your experiences as a teacher, how long have you been teaching?

I am beginning my 16th year teaching at Washington University in St. Louis, in the Sam Fox School of Design and Visual Arts. I taught one semester at Parsons before teaching at WashU, but those students should ask for a refund—I didn’t know what I was doing at all!

In 2019, along with fellow Professor, D.B. Dowd, we started a new graduate school in illustration, MFA Illustration and Visual Culture. The program is completely unique. It explores the idea of illustration authorship by combining studio practice in illustration/comics with academic and archival based training in visual and material culture. Students immerse themselves in DIRA, (Dowd Illustration Research Archive) which is a treasure trove right here at WashU. It is a vast repository of original illustrations, magazine, comics and visual ephemera from the 19th and 20th century. We focus on good writing, attracting students with a lens towards studio practice, authorship and academia.

What do you feel the role of an instructor is?

There has been quite a bit of conversation recently about educational models in art and design schools. I think there are twin roles of a professor in a design classroom: challenge and nurture. It is very hard to make art, and students need faculty who long to understand not just what they made, but what they intended to make. I strive to both critique the ‘artifact’ on the wall while also listening to what the student’s goals and ideas are at the same time. The four years of art school should really be spent closing that gap between a student’s intended goals and what the object is actually communicating. Cultivating a student’s visual voice has nothing to do with me or my interests. Though I can help introduce a young artist to new approaches or new artists, the outcome of the work they make should be a process of self-discovery. In my mind, goals of a liberal arts education should be (H/T C.S. Lewis):

1. The pursuit of truth

2. The discovery of self-knowledge / practice of self-discipline

3. The cultivation of virtue

How are you able to juggle teaching with your editorial work and books?

When I figure it out I’ll let you know. I’ve been taking less editorial work as I’ve been focused more on my long-format authored works, but I really do love editorial and miss it! So, call me anytime for that magazine cover, New Yorker! That is my all time bucket list editorial job.

What is your advice to graduates entering the field today?

I wish that when I left school I realized how long a career in illustration really can be. I was so eager to have instant success (and by instant, I thought a year or two was an eternity) when I entered the field at age 23. But, the truth is that to have success as an illustrator you have to have patience and persistence. It just takes a while to learn how to master your craft and to be able to know what you have to offer to the world. That isn’t to say that you need to become ‘perfect’ before you start promoting yourself, the very opposite in fact. You have to make work that you enjoy, even if it doesn't seem particularly ‘marketable.’ I think editors and art directors are attracted to joy, and it shows when you enjoy your work. Also, remember, to get a big break you don’t have to convince 1000 people to believe in your images, your stories, your ideas …. Most of the time you have to get just one person to take a chance on you. One person can break the field open for you.

What advice would you give to teachers?

Most students are not primarily looking for data and information, but mentorship and a relationship with a credible role model who is a working illustrator. It took me a long time to learn that sometimes the best act a teacher can perform is to merely listen. We often feel like we have a duty to provide “answers” to our students, and it is so tempting to act as an ‘art director’ and tell students what color to make something or that they should ‘try adding a hat on the rabbit.’ But, if you answer their questions with a question back to them, and interrogate not just WHAT they made but HOW they made it, and finally WHY they made it. If you can pull on those threads, self-discovery and visual voice will follow. Ultimately, art school should not give students a great portfolio alone, the real thing they take with them is a process. The portfolio will be outdated in a year or two, but it is a healthy process that allows them to continue discovering themselves for the rest of their lives.

Final words to practicing illustrators?

Carry a proper sketchbook. Even if it is a bunch of copy paper or post-it notes stapled together, it will keep you off your phone.

Is there anything you have a hard time drawing?

Horses. Spiral staircases. Bicycles. Or the worst possible combination: a horse riding a bicycle down a spiral staircase.

Find me:

John Hendrix Illustration

john@johnhendrix.com

917-597-6310